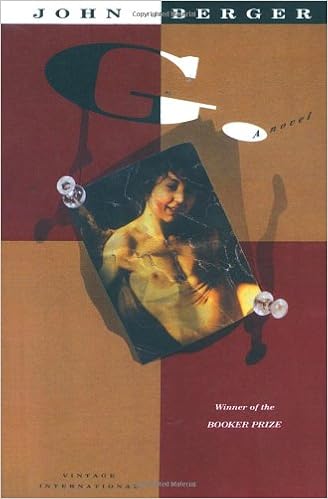

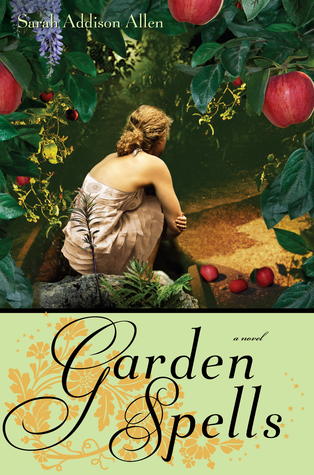

What I thought of this book changed dramatically every time I sat down to read it. One time, I'd be utterly charmed by the characters and the small town, but then the next we'd have characters who seemed to be operating from such bizarre premises that I would get irritated with them beyond measure. I went back and forth, and it never stayed the same. In the end, I enjoyed it more than the main characters bothered me.

Part of what bothered me was this: neither of the main characters, two sisters, have anyone they talk honestly to. Not one. I get that you're trying to show they're isolated, but seriously, not one? Given the fairly tame level of "eccentricity," that alone strains belief. Because they don't have a single solitary person they talk to honestly, neither of them has someone to say to them "hey, you know how you think X-Y-Z with absolutely no proof? Maybe you're not right?" The characters wouldn't have to necessarily listen to the reality check, but if the reality check was there, at least I would know the author doesn't think this is perfectly normal behaviour.

If she does, I'd be a little terrified.

So, you have two sisters. Their mother was a erratic and died fairly young, so they were brought up by their grandmother, who by all accounts was stable and loving, even if regarded as a little eccentric in her town. (For eccentric, read charmingly magical.) Despite this stable influence, both sisters are fucked up in a way that seems disproportionate. I'm not saying having an unsettled childhood until you're six doesn't leave some scars, but there just seems to be no sense of proportion.

The older sister was jealous of the younger, as she seemed to be the reason she and her mother stopped living in cars and homeless shelters. During her teenage years, she was not very nice to her sister, although we're given no really concrete examples. Again, I get that that can leave some wounds, but ones this big?

The older sister has grown up in the town by herself, her sister left long ago, and her life is entirely isolated from everyone around her. She had zero friends in high school, no friends at any point afterwards, no one she has much point of connection to, even though she's a sought-after caterer because her meals are literally magic. She's so closed down about people leaving her and needing stability she's practically non-functional.

Now, I get that. But as a reaction to what she's actually been through?

Okay, fine. But seriously, I kept wondering how exactly she got THIS fucked-up. I would have happily have accepted a level of fucked up that was that she didn't want relationships, but otherwise had a friend or two. It didn't ring true with how the character was written, which was as a charming young woman who was a little fussy. I know people who are afraid of being rejected or people leaving them. They may have difficulty doing so, but they all reach out to someone.

The younger sister wanted to be more like her mother, ran away from home as a teenager, and got into an abusive marriage. She runs away with her daughter, and similarly, makes all these assumptions about her sister without ever once checking in with reality to see if they are anywhere close to true.

Okay, yes, as the book goes on, they start to trust each other and open up, and it's lovely and heartwarming. I just...I can't help feeling you could have that without the extreme emotional level of the assumptions they were making about each other. It rang so false that it was hard to read the reconciliation as true.

Still, there are very charming bits of this book, a couple of sweet love stories. I would like it if that sweetness were paired with real difficulties, not ones that feel like they were made up just to create barriers between people trusting each other. Everything, at the ends, dissolves so easily into happiness it shows how artificial it was to begin with.