People

recommend books to me a lot. It's hard to know when or how to fit them

all in! And then there's the worry I won't like a book that is very dear

to a dear friend's heart. For a long time, I just avoided reading books

that had been recommended to me, unless someone pushed a physical copy

into my hot little hands. (This is still the fastest way to get a book

to the top of my list.) So I started a new list to read of books friends

recommended. If you want to get in on this, you can recommend a book

on this post.

This book was recommended to me by Matt

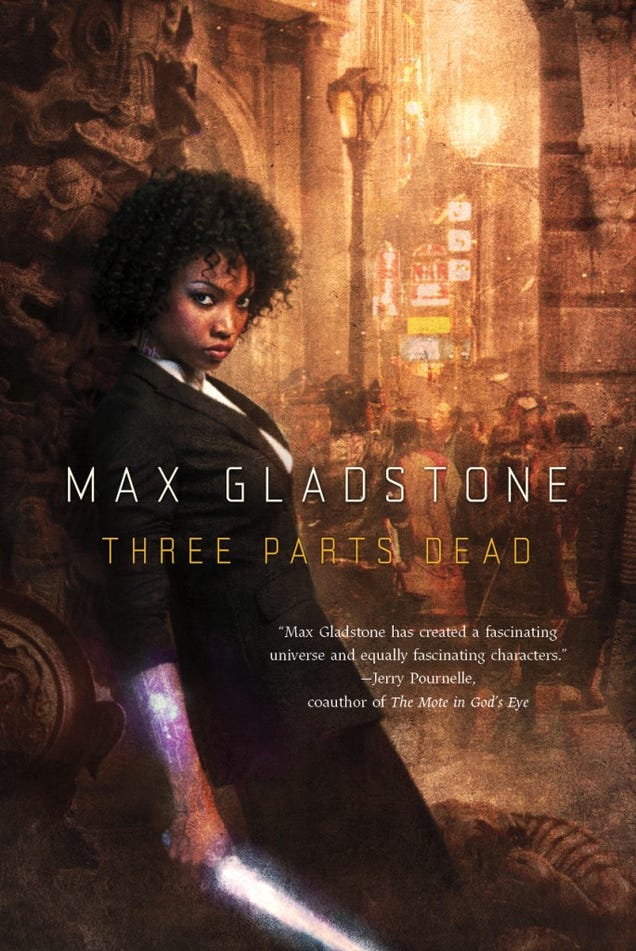

Imagine magic as being something very much like the law - if you make a good enough argument and have the documents on your side, you can change the world. That's part of the premise of Max Gladstone's Three Parts Dead. When a god is killed in one of the last places to even have a god, lawyer-magicians on two sides show up to fight it out over how exactly he'll be resurrected, according to which contracts, and depending on what liability can be proved.

This book was recommended to me by Matt

Imagine magic as being something very much like the law - if you make a good enough argument and have the documents on your side, you can change the world. That's part of the premise of Max Gladstone's Three Parts Dead. When a god is killed in one of the last places to even have a god, lawyer-magicians on two sides show up to fight it out over how exactly he'll be resurrected, according to which contracts, and depending on what liability can be proved.

This sounds like something that, in the wrong hands, could be very dull, but it is not. Gladstone has created something here that is most similar to Earthbound urban fantasy, but set it in an entirely other world, one where humans figured out how to harness the beliefs that gave gods their powers, and bound it into contracts and power. This caused a war with the gods, in which most of the gods died at the hands of the upstart humans.

One city's god had no part in the war, although his lover joined and died. Just as the dust is settling, many years later, Kos the Everburning turns up dead. An associate from a magical necromantic firm takes on a new apprentice, Tara, who had been a student at the school for magic, but was tossed out (literally, given that the school floated above the clouds and she was unceremoniously dropped over the side.)

The counsel for the opposing side was the professor who dropped her over the side of the school to, presumably, her death, so she's got some scores to settle. But mostly, she needs to prove herself. Tara is an interesting main character - she's so invested in learning a kind of magic that will eventually strip the meat from her bones that she is willing to forsake family, connection, and almost anything to get back into that world.

Driven as she is, though, she's still sympathetic, human enough to be horrified at what one of her professors had "accomplished" to try to take him down. She's clever, and in way over her head, but knows enough to enlist the chainsmoking monk who was present when his god failed to show up, the monk's childhood friend, now an agent of Justice and also a vampire bite junkie, and a vampire pirate captain.

This book was a great deal of fun, while also having some things to say about power, about religious presence, and the effect of the void on those who once had it filled and are now looking to reclaim what made them feel whole.

Add in to that some ravenous shadows, another murder, a gargoyle who has his face stolen from him, along with his will, and some pleasing twists and turns that you'd expect from a book that, after all, hinges on something like a court case. There's plenty of action as well, particularly when the gargoyles are involved.

The concept of Justice as it is expressed in this book was particularly intriguing - after Kos' lover was killed in the war, she was resurrected, but only partially - everything that made her a goddess, a personality, or capable of bestowing grace on her followers, was stripped away, and she was turned into a force that is only concerned with tracking down malefactors as designated by the contract that brought her back. When the officers are in the grip of Justice, they lose all sense of self and get a touch of wholeness, but always without the core of connection that would make it something warm. This is what leads the officer we meet to seek out the addictive pleasures of having her blood sucked by vampires, because otherwise, she is always empty when she isn't on the job.

I don't know if this one is for everyone, but this was definitely a fantasy book meant for me. I'll be looking for the others in the series.